Environmental concerns have gained significant attention, leading various entities to adopt a “green” label in their communications to attract conscientious consumers. However, not all sustainability claims are genuine, giving rise to “greenwashing,” a term for deceptive marketing strategies that falsely portray products, services, or initiatives as environmentally friendly. These deceptive tactics often fall under the umbrella of “The Greenwashing Hydra”, a framework defined by Planet Tracker1. that identifies 6 sophisticated marketing strategies.

Greenwashing can occur easily, often driven by the allure of appearing environmentally conscious without making substantial changes. It involves rebranding existing practices with eco-friendly labels (Greenlabeling), changing the targets date and numbers (Greenrinsing), downplaying broader sustainability issues while emphasizing one positive aspect (Greenlighting), and employing various marketing strategies to create an illusion of environmental friendliness. This issue is particularly relevant during massive shopping events like Black Friday and Christmas, where consumers seeking eco-conscious choices may inadvertently support greenwashing.

H&M – when fast fashion wants to be sustainable

In 2011, H&M launched a new clothe line “Conscious”. Behind this name, an engagement.

“Our aim is for all our products to be made from recycled or other sustainably sourced materials by 2030. This actually already applies to 80% of the materials that we use. We also have Conscious choice: pieces created with a little extra consideration for the planet. Each Conscious choice product contains at least 50% of more sustainable materials — like organic cotton or recycled polyester — but many contain a lot more than that.”2 .

The claim is appreciable but is a “Greenlighting” – we only talk about the material, not the quality, the production process, the energy, the social impact, or the water consumption. They spotlight a green feature of their products in order to draw attention away from environmentally damaging activities. In addition, it contains vagueness with the use of “more”, “little extra” and “a lot more”.

Volvic – don’t burry your water bottle in the garden

In 2011, Danone launched a new bottle called “Bouteille végétale” for Volvic. In a TV spot, they compared it to a salad or a cactus. The company claimed that 20% of the plastic was made from vegetal material. Indeed, it was true, but the resulting product was just a BioPET using the same molecules, leading to the same “end-of-life” issue as a regular plastic bottle.

It’s a clear example of “Greenlabeling”. It was not compostable, nor bio-degradable like a vegetal material, and was actually toxic for the environment.

Since then, Volvic has used a different strategy and is now offering bottles made from 100% recycled materials.

Shell – what are you ready to do to help reduce emissions

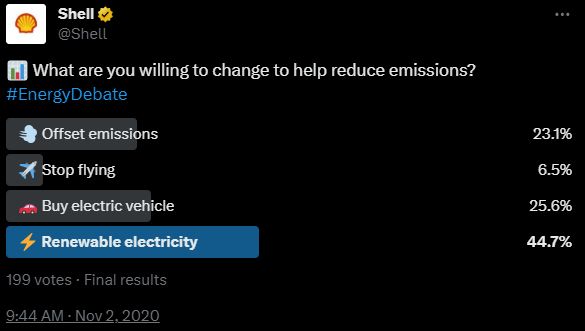

As a final example, Shell, a British multinational oil and company, asked in 2020 its customers what they were ready to do to help reduce emissions.

By doing so Shell, is doing “Greenshifting”. They imply that the consumer is at fault and shift the blame on them. Shell is considered to be the 6th biggest contributor to Greenhouse Gas emissions for the industrial area, accounting for 30,751 MtCO2e, or 2,12% of the global emissions3. In addition, a company’s 1991 movie4, titled “Climate of Concern”, showed pretty clearly the global impact of fossil fuel burning. But they didn’t do anything to change the narrative.

Regulations and Accountability: The Fight Against Greenwashing

In Europe, those issues have prompted legal discussions and initiatives to tackle deceptive environmental claims. The European Union (EU) is working on stricter regulations for environmental marketing and sustainability labeling. The “Directive on Green Claims”5 aims to make green claims reliable, comparable, and verifiable across the EU, and protect consumers from greenwashing.

The EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) promises to change the landscape by requiring large and/or listed companies to publish comprehensive, standardized sustainability reports as of 2025, further enhancing transparency and accountability.

The power of the consumer

The prevalence of greenwashing creates a “Sustainability Deception Loop” that perpetuates consumer misinformation and reinforces unsustainable consumption patterns. This cycle not only undermines the credibility of authentic sustainability efforts but also hinders progress toward a more environmentally conscious society.

“Greenhushing” is the most recent trend in greenwashing. It refers to the idea that organisations deliberately choose to under-report or hide their green credentials from public. It can be used by both companies doing efforts but being afraid to be accused of greenwashing, and most frightening, companies doing nothing and avoiding scrutiny. We will go from an over-communication to a complete absence of communication and the consumers will have to be more and more vigilant.

Breaking free from the greenwashing cycle requires not only stricter regulations and transparent labeling but also a shift in consumer awareness and choices. As consumers become increasingly discerning and demand transparency, they can play a pivotal role in disrupting the model.

1 Planet Tracker is a non-profit think thank focused on sustainable finance.

2 https://www2.hm.com/en_gb/customer-service/product-and-quality/conscious-concept.html

3 Page 26 of the Carbon Majors analysis, https://www.climateaccountability.org/pdf/MRR%209.1%20Apr14R.pdf

4 https://thecorrespondent.com/6286/if-shell-knew-climate-change-was-dire-25-years-ago-why-still-business-as-usual-today/692773774-4d15b476

5 https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/circular-economy/green-claims_en#timeline